Angelica is available for preorder from your local bookstore, OR:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Angelica is available for preorder from your local bookstore, OR:

In Michoacán, the migrating mariposas appear with November, as if trailing the marigolds trucked in for Day of the Dead. They come by the fragile millions, fluttering a few thousand miles from el norte to the transvolcanic range of their own origin. As such, the monarcas are seen to symbolize the annual returning of souls, they are the mascot of the local soccer club, and their patterned wings fan Mexico’s migration myth. In Mexico, they became my own myth and mascot as well.

Like these monarchs, I wasn’t hatched in Mexico, but in the Great Lakes region, where there is such abundance of milkweed lining roadsides and reclaiming fallows. As a child I scattered seeds from dried pods and smeared my hands with the sticky white sap that bubbled up like blood when I ripped a leaf or snapped a stem; the glands in my throat recall the bitter milk, my fingers the tack. I remember the monarchs also. I captured their fleshy pale green-and-black striped larvae, let them march up my ticklish arms on their stub legs. When I got older, I ran through weedy hayfields to net the winged adults. I practiced holding my captives just-so so the scales would not wipe off as I fed them sugar water, unfurling their proboscises with a sewing needle.

While in English butterfly has etymologists stumped, the ancient Greek word is psyche, the same as soul and breath. In Spanish, the word is mariposa, which is theoretically derived from the phrase “Maria, posa,” or “Mary, alight.” But in the days of my butterfly safaris through timothy and alfalfa it did not occur to me to reflect upon the “thread of vital light,” upon mortality, even as I imposed it with my sticky fingers and forced feeding.

Now that I’ve reached my adult life stage (however delayed it was coming), and am vaguely more aware of the damage I do to the world with my insatiable curiosity, more aware of the work of survival, it smarts to know how far those monarchs that I befell had traveled before they suffered at my hand. They were then just butterflies, mere ephemera bobbing from one bloom to the next, but they had, I realize now, a purpose beyond those flowers, a direction, a destination, even a grand design…

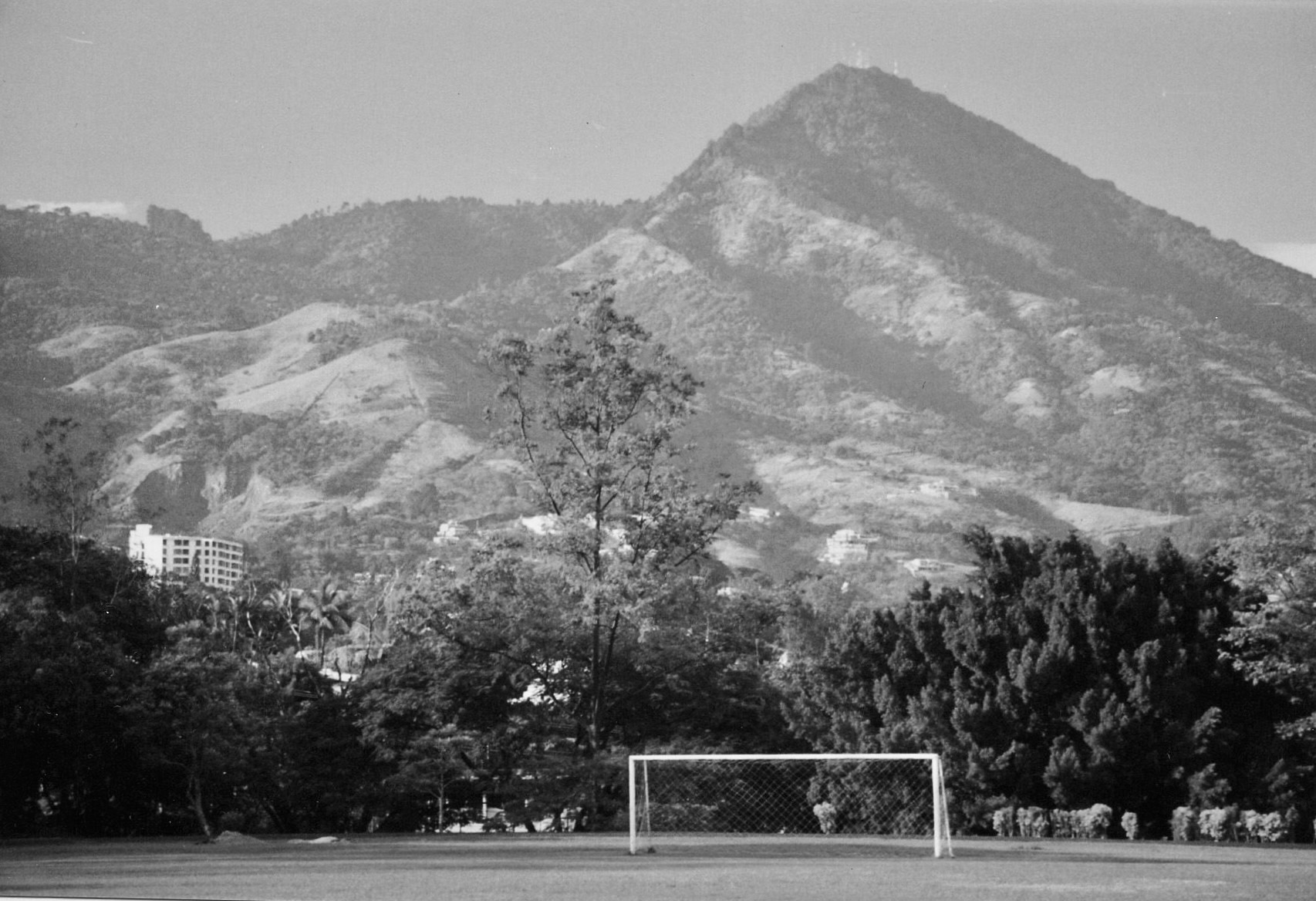

According to the Gospel of Luke, Jesus was born while his parents were traveling to Bethlehem to register, as required by law, with the census. Fast forward 2,010 Decembers— giving or taking a few for the ecclesiastical debate and/or shoddy recordkeeping around the dawn of the common era—to the advent of my own son’s nativity. He wasn’t born in a Bethlehem barn beneath a great star but in Michoacán’s Star Médica hospital overlooking a bullring.

19.7°:101.2°; 20:23 hours; masculino; 2 kilos, 250; Apgar 9. The data of birth is quantifiable; a baby is weight, gender, and geography.

Too soon, I knew, he’d be more data. Too soon, we’d have to begin the process of certifying his identity, of classifying and designating and documenting a being who still felt like an extension of my body, our umbilical joining a residual cord, a phantom itch, a short in my circulatory wiring. But in those dim, reverential days and nights after his birth, my son did not exist anywhere but in my arms; he was nothing but sweet breath and drying flesh, his tiny fingers and toes printed with patterns unfiled anywhere. He had no name or nationality. Not on paper anyway. Not in Mexico, where the birth certificate would not be processed by the hospital, but by a public registry, which was of course closed for the holidays: el día del Virgen de Guadalupe, la navidad (y, for the bicultural kids, el día de Santa), and Three Kings’ Day. My child belonged to nobody but us, his family, to me and his father and his one older brother.

The past could be jettisoned… but seeds got carried.

Joan Didion

For my birthday this year, my five-year-old son presented me with a sequoia seedling just four inches high. Sequoia as in, Sequoiadendron giganteum—the Sierra redwood that, given a couple millennia, can grow to be one of the largest living organisms on the planet. It came, this fragile sprout of evergreen, in a clear plastic tube emblazoned with assurances that this tree could and would GROW ANYWHERE!

This gift was not entirely far-fetched. That February weekend, in Sequoia and Kings National Park in Central California’s not-so-nevada Sierra Nevada, we had visited several named trees—Generals Sherman, Lee, and Grant still looming large on our western flank—and we had walked the hollowed-out length of one fallen specimen. In every grove, I had exhibited intense enthusiasm for the magnitude and grandeur of these trees, the pitch of my euphoria approaching that of John Muir himself (this from a letter he wrote in purple sequoia sap):

See Sequoia aspiring in the upper skies, every summit modeled in fine cycloidal curves as if pressed into unseen moulds, every bole warm in the mellow amber sun. How truly godful in mien!

I can’t speak for Muir’s rhetorical purposes, but my exuberant performance was intended mostly to move my children, who at three and five are wholly unsurprised that objects in the world are larger than they are. I badly wanted them to know and remember that we were visitors in a rare and significant place; I wanted to rouse in them a worthy state of wonder.

My older son had observed these antics of mine and arrived at the perfectly logical conclusion that his mother was as crazy about giant sequoia trees as he was about Legos and dragons. So when he saw that real, live sequoias were sold at the park gift shop, he knew what to do, and he wore his father down.

“Isn’t it just what you always wanted?” my son wanted to know the moment I pulled the tube-tree from its paper bag, his eyes glittery with the pleasure of there being a present in our midst….

In those first months living in El Salvador, had I walked down a village street and seen young men leaning against gaping doorframes, their eyes steady upon me, I would have read the wrong story. Then, I could barely speak, let alone interpret what signs I might have seen: a flash of black ink on skin; aerosol piss scrawled across cinder block walls. I might have misremembered that those men catcalled, that they hissed. I would have seen cliché, not clique; the awkward beat of sex lost in translation, not the tick-tock of a multinational time bomb.

My tenth grade students were no help. They spoke abstractly of comunistas, and, more concretely, of the kidnappers who lay in nebulous wait for them, should they venture beyond their opulent sphere of bodyguards and bulletproof BMWs. They—bilingual and bicultural, if not tri-, or more—understood far better than I how meanings shift according to association.

“Miss, what does your tattoo mean?” they asked about the blue moon at my nape. They never mentioned—and I relied on them for information—that body art is probable cause in El Salvador, that it came with a twelve-year prison sentence. In fact, they never spoke of maras, of mareros, of gangs and gangsters. Maybe they couldn’t see either, although I doubt that. I think they thought the maras unspeakable.

When I’m out of words, out of context (as I was so often in Salvador), my memory turns visceral: I remember the oozing feel of warm bottom sludge. I remember the way my body glowed an eerie white in the moonlight, the stark contrast of my skin against greased black water, a shard of bone upon obsidian. I remember how hard my heart beat.